What was your first architectural job?

I did a year in practice as part of my undergraduate degree at Edinburgh University, which was split over two 6-month placements – the first was a small practice in the Netherlands, and the other, back in Scotland. The placement in the Netherlands was with two friends and it gave us the perfect opportunity to live in a new country and experience a different culture for the first time which was a good part of the experience.

What inspired you to go into architecture?

For as long as I can remember I always said I would be an architect. We had a neighbour who was a family friend, who was an interior architect. I always remember being fascinated by the stories she would tell me. I was very into drawing and crafting things when I was young, making delicate model aeroplanes with my dad, or making birthday cards with my mum. She was doing a degree in decorative arts at the time so I recall doing printing and glassmaking with her.

What do you think is the biggest challenge for the architecture industry and why?

I'm currently working on a project on site, so looking at the question through that lens, the thing I hadn't appreciated before this project is the diminishing role of the architect. On a design and build contract, we are often not at the centre of all the conversations, whereas when I was doing my Part III, everything was fairly focused on the traditional method of procurement where the architect is much more central to the process. I think that is a big challenge, and I hope, and think that we as architects need to get back into those conversations and meetings where things are decided. We need to be able to champion good design - I guess it is about trying to work out how we can continue to do this while also being mindful of the commercial conversations and decisions that are happening.

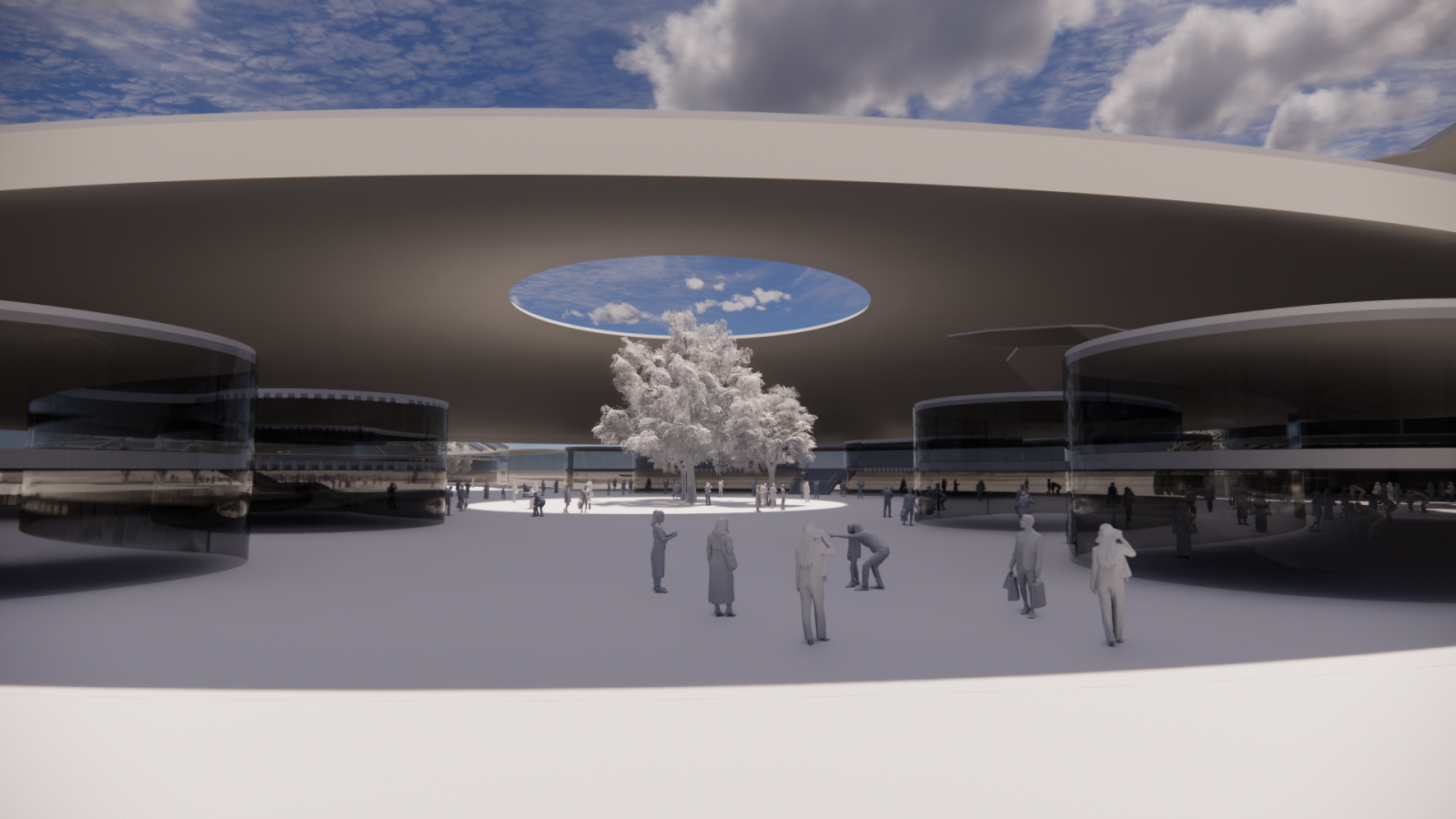

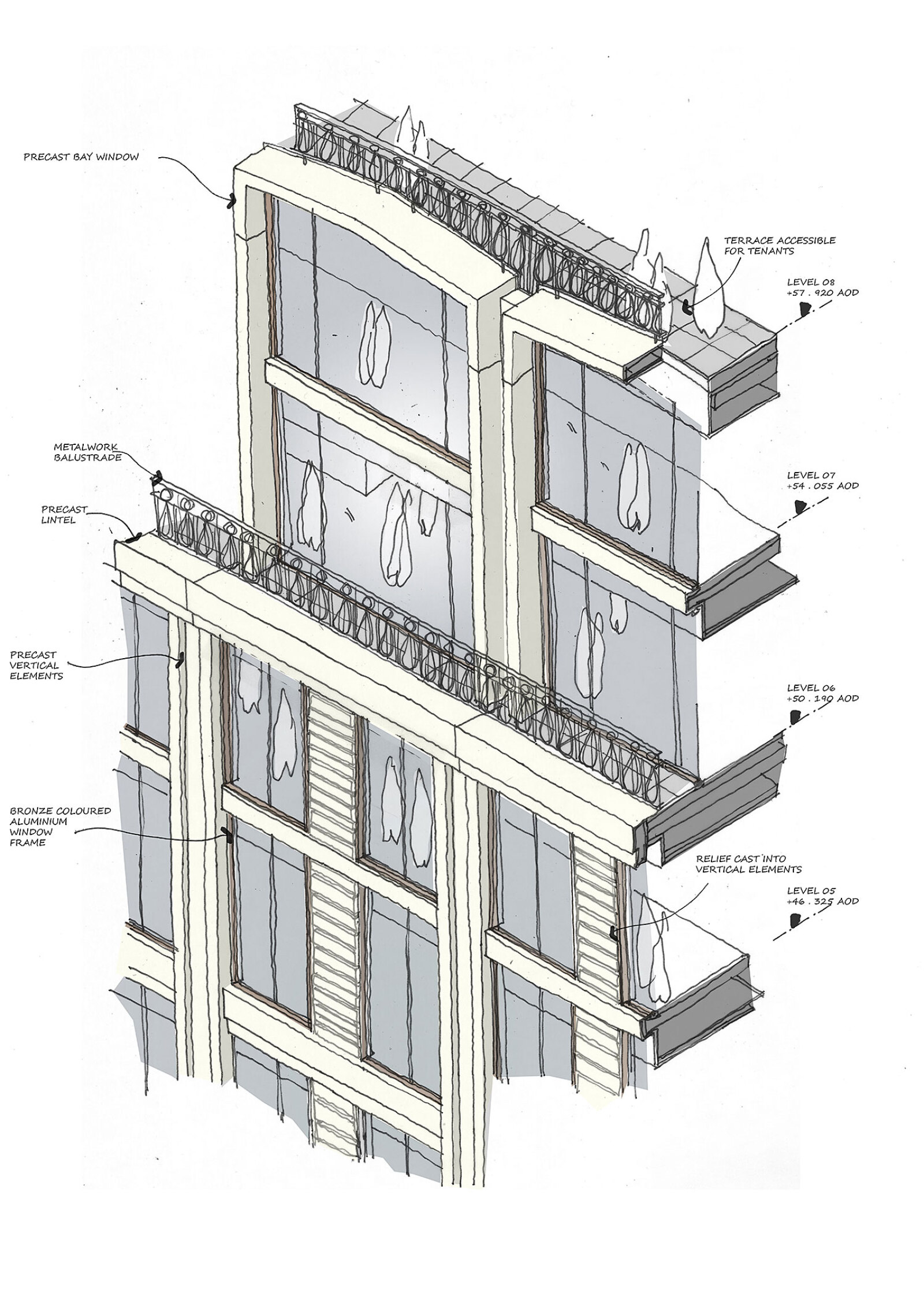

The Earnshaw

I started my undergraduate degree 10 years ago and finished Part III just over two years ago, so I don't think I've had that long to have done anything differently. I have worked at Apt for four-and-a-half years now which I have really enjoyed. Being here for that length of time has given me the chance to grow into my role of an architect. Potentially I would have liked to have lived abroad. I really enjoyed the six months in the Netherlands and going somewhere else for a longer period of time is something that still interests me, but I have many years ahead of me to do that.

What could be done to make the architecture profession more accessible?

To make the profession more diverse, I think it really must start in school, opening up architecture and educating children on what ‘architecture’ really means, so when it comes to discussing the jobs children aspire to have, it becomes part of the conversation. Financially, something also needs to change to make it more accessible. Looking at a 7-year trajectory is enough to put a lot of teenagers off when starting their UCAS journey.

Working in practice and especially on site has really opened my eyes to just how male-dominated architecture and the wider construction industry really is. The dropout rate of women in architecture is astonishing, with the ratio of men to women starting around 50% in university but drops off to around 30% of registered architects. This appears even less to me, when looking at more senior roles within practices.

If we can address accessibility, increase diversity and encourage retention in the profession, it will improve our designs. Places are made for everyone and if you only have a small subsection of people designing those, will they truly be inclusive? Of course, you must be mindful of people while you design, but there's no real replacement for learned experience.

No, but I'm not sure how you would teach that! One thing university education is particularly strong at doing is teaching you how to learn. Every situation you come across is new. It can't all be taught, so it’s important that you develop ways to approach challenges. Throughout Part 1 and 2 try to get site experience and learn from the specialists - the sub-contractors and consultants. That's where so much site-specific learning comes from.

What advice would you give to any young person who is about to start a career in architecture?

The main one for me is the importance of maintaining interests outside of architecture - those things you are really passionate about before you start studying - keep them going. It is quite a challenging education and if you're not careful it can take all of your time. During Covid I rediscovered enjoyment in crafting and making things. It's so important to keep those other interests alive. It makes us better designers; happier people and it helps to give perspective when things can seem a bit tough early in your career.

I have been working on the Earnshaw, a commercial building in central London just off Tottenham Court Road, for the last three and a half years. It's 10 storeys of commercial office with retail at ground. It has been a fairly long journey, all of my qualified professional career, so I have seen it through a number of work stages. For the most part I'm enjoying it but it's not without its challenges – I’m rising to these and seeing them as opportunities to learn.

During your time at Apt you have had the opportunity to see a large and complex project through a number of RIBA work stages, and now onto site. I imagine it's been a learning curve – what do you think are your biggest lessons learnt?

One of the big things that I've learnt being onsite is the importance of scale. Now everything is digital, we can get caught up in the never-ending zooming in on drawings. But ultimately somebody has to build this, so while you might be zoomed in on a tiny, specific detail, you have to step back and realise things are drawn to a specific scale for a reason. Whenever we go onto site it helps me reframe what I've been drawing, against the realities. Being able to put the two together is really important - to keep sight of how things are actually built. Then tolerance comes into play. As things are built, we have to allow for movement, and very few things are millimetre perfect. It could be raining on site - there's a lot of disciplines working together, and the reality is that things won't be exactly as per the drawing. We must design to reflect the onsite conditions. There's no point drawing something that can't be built.

Is it difficult working on the same project for such a long time? What keeps you motivated?

It can get difficult. You can get caught up in the small stuff and forget the bigger picture – we are building something pretty cool and are part of a team creating a building that will be here for decades to come. Having a really strong team around you helps. This team has varied over the years, but I think one thing that has always stayed true is that we have been able to have fun. It wouldn't be as good otherwise.

I have really enjoyed working on a commercial office space. I think that it's an interesting time for this sector. Post-Covid, people are asking a lot more of their workspaces. I would like to go back to the beginning, to see what happens on a commercial project in its early design stages, and how that differs from the work I'm doing now. I think there's a lot more required now in terms of sustainability, wellness, and the types of facilities you design in alongside the more general office space.

Finally, if you weren’t an architect, what do you think you’d be doing instead?

I think I would be doing something with my hands. The cliché is designing it and making it. That would maybe involve furniture design, woodwork, or metalwork. But I don’t know if I’d prefer that or not – sometimes it’s nice to keep things as a hobby and not turn it into a profession. When you monetise things, you risk losing the joy.